The purpose of this short article is to provide a common ground of notions and knowledge on SaaS metrics, based on the hundreds of SaaS companies we see and evaluate on a yearly basis at Qualgro.

We hope that this will help everyone in the ecosystem (founders, advisors, VC friends) to speak the same language and normalise expectations and understanding when tackling SaaS businesses.

Let’s take a simplified example to illustrate: you are a SaaS company with one product and two price tiers at US$100 and US$50 a month, respectively (for example premium and basic plan). We are in January 2021 and as of December 2020, you have 10 customers paying each US$100 monthly subscription fees, thus generating US$1,000 in subscription revenue.

What are the key metrics you should be tracking to ensure right understanding of your business and sustained longevity of your company?

The following are definitions of the main B2B SaaS metrics you should be monitoring for your company in the context given above. Note that all these metrics can, and should, be tracked across various different levels: company level, product level, cohort level, customer group level, etc.

Level 1 metrics

GM= Gross margin

This might sound obvious, and while GMs are not specific to SaaS businesses, one of the key reasons why SaaS has been so popular in the recent years as a business model and has also received so many investments, is partially due to the very attractive GMs SaaS businesses are able to generate — at least 80 per cent.

Net MRR= Monthly recurring revenues

This metric is always linked to a particular month (e.g. MRR of January 2021) or a period (e.g. average MRR for Q1 2021). The word ‘recurring’ is extremely important here: MRR is what customers are paying on a monthly— hence recurring — basis. This is basically the subscription fee to your service (think Netflix at US$8.99) and excludes any one-time fee such as POC, setup, maintenance etc.

Some of these revenues might be recurring (e.g. maintenance fees), but they do not bear the same economics and stability as your subscription revenues. These costs will still add up to your total monthly revenues. If your customers pay upfront for a given duration of usage (e.g.: 12 months in advance) then your MRR is the total revenues divided by the duration of usage.

Also Read: 4 Simple ways to cut your customer acquisition costs

Depending on how quickly you onboard your customers or how long they take to pay, you might want to track actual cash MRR vs. other MRR (e.g. contracted MRR, invoiced MRR, etc.).

(Gross) MRR $ churn= percentage of loss of MRR in $ from existing customers compared to last month

For instance, in December 2020, you had 10 customers each paying US$100. If one customer stopped paying in January 2021 and another one downgraded to your US$50 tier, your MRR churn is -15 per cent (-US$150/ US$1000).

A quick point to note: some people would rather use net $ MRR churn = $ churn — expansion (i.e. existing customers increasing their spend). In our opinion, one of the issues with looking only at net $ churn is that it hides some information. For example, you could think all is well by just looking at a negative net $ churn (basically your revenues are increasing).

In this scenario, while some customers increase their spend, you are still losing other customers and you might not be focusing enough resources on how to retain them.

Logo churn = percentage of loss of MRR in number of paying customers compared to last month

In the same example as for MRR churn, your logo churn is -10 per cent (one lost customer/10 existing).

ARR = Annual recurring revenue

This is simply 12 times the MRR of the month you are looking at (e.g ARR as of January 2021 = Jan 2021 MRR x 12) — nothing more, nothing less. Again, don’t forget to exclude any one-time fees/non-subscription revenues.

CAC = Customers’ Acquisition Cost

This is where you add all the costs incurred to acquire new customers: marketing ad spend, discounts, marketing and sales staff salaries etc. There is no absolute value of “good” or “bad” CAC but there are ratios that are useful to track (see Level 2 metrics).

LTV = Lifetime value (of a customer)

This is how much revenue a given customer will generate before churning. In our example, if a customer churns after 18 months (without changing price-tier) then his/her LTV is US$1,800.

Level 2 Metrics

Now that we have defined the main metrics to track as KPIs for your business, here are some level 2 metrics that are more reflective of your company’s health and (growth) trajectory. These are also the very metrics that potential investors will normally look at in detail, while considering an investment in your company.

Growth rate

Usually measured on the net MRR or ARR, the growth rate indicates how fast you are expanding your business. In early-stage startups in SaaS (e.g. from Pre-Series A to Series B), we usually expect companies to grow at least two–three times year-on-year— and even more for seed stage companies.

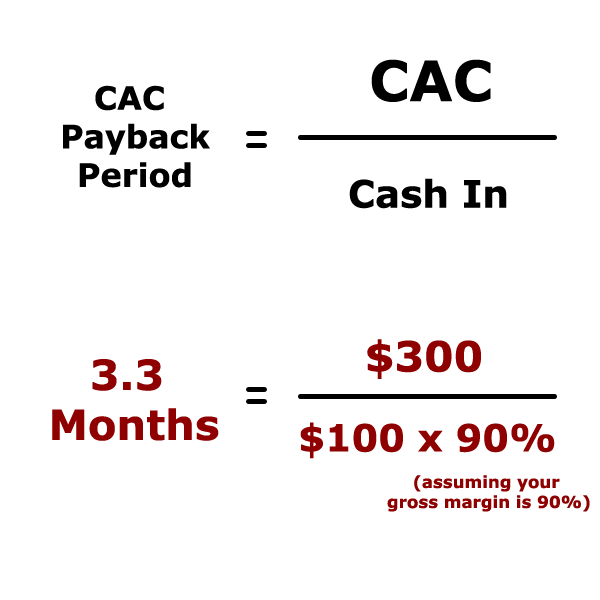

CAC payback period = CAC / cash in for a given customer or group of customers

This basically indicates how much time a given customer takes to pay back their cost to be acquired. In our example, if your average CAC is around US$300 and your gross margin around 90 per cent then the payback period is US$300 / (US$100*90 per cent) = 3.3 months for a customer to “repay” its acquisition cost.

Usually, you would like your payback period to be less than the duration it takes to acquire customers on average. However, sales cycles tend to be longer for B2B sales than compared to B2C products, so payback periods of six months or more are not uncommon.

LTV/CAC ratio: this ratio is used to assess the efficiency of your acquisition efforts

A high ratio means you’ve found effective ways to acquire customers without spending too much. However, if it’s too high, it could mean you might not be spending enough money on acquiring customers. If your ratio is too low, it could mean that you’ve spent too much on a customer that doesn’t bring much to the company in the long run.

There is no “ideal” LTV/CAC ratio (although 3:1 is usually a good start) but by all means this should be higher than 1:1.

Also Read: Customer churn can kill your startup

Cost base: this is basically what your company is spending to operate and grow

While some people might look at the so-called burn rate = cash need “after revenues” (= revenues — costs), at Qualgro we usually look at your full cost base. For example, if we assume that your only costs are your salaries and they amount to $1,200 a month, we would assess your cash needs for year 2021 as US$1,200 x 12 = US$14,400.

Some others could say that your burn is $1,000 (revenue)— US$1,200 (cost) = US$200 on a monthly basis and you would need only US$200 x 12 = US$2,400 for year 2021.

The rationale for us to look at the full cost base without revenues is that early-stage companies have quite unpredictable revenue streams by design — even in SaaS— and knowing the real cost base of the company enables everyone to anticipate better the full cash needs to sustain in the medium term, even if revenues drop to 0.

As a matter of fact, 2020 was a good example of basing your cash needs on your full cost base and not just your “burn” (and provisioning cash closer to US$14,400 than US$2,400 in our example).

Putting things into perspective: Valuation of SaaS businesses in Southeast Asia

No article on SaaS metrics can go without a word on valuation. While some people would argue that valuing a business is more art than science, and without providing a “magic number” (hint: there is none and each company is different), we think that some common guidelines should be followed by the ecosystem to normalise everyone’s perspective on SaaS valuations in the region.

As Southeast Asia is a region and market on its own, with limited comparison possible with US, Europe or China, it is important for every stakeholders (founders, advisors, investors) to understand the intrinsic value of each business with its own characteristics and KPIs (hopefully with the help of the lists above), and not to try to copy-paste valuation multiples from other geographies as “market standard”.

On using public SaaS companies as benchmark

Valuing a private company is different from valuing a public company and using public companies’ multiples (whether revenue multiple, P/E, etc.) while providing some data points, cannot and should not be used as-is to price a private company, especially a startup in its early years. The list would be very long but the range of metrics are altogether very different: size of the customer base, consistent growth over time, product breadth and depth, etc.

On using forward multiples

These have in our opinion no business reality— valuing a business based on a multiple of one of its metrics (MRR, ARR, EBITDA, etc.) is already taking into account upcoming growth. Applying a multiple of “expected ARR’’ for the year to come is basically counting twice the effect of planned growth into the valuation.

On using US multiples for Southeast Asian companies

The US market is very different compared to SEA: maturity of the companies and customers, willingness to pay for SaaS products, size of the market, talent pool, etc. Keep in mind that the multiples used to value US companies are intrinsically tied to the local context of the market and the size of the opportunity, which is starkly different in SEA compared to the US.